Ms Pouleur Received a Bachelor of Arts From Barnard

| |

| Latin: Barnardi Collegium | |

| Other name | Barnard |

|---|---|

| Motto | Επόμενη τῷ λογῐσμῷ (Greek) |

| Motto in English language | Following the Way of Reason |

| Type | Private women'southward liberal arts college |

| Established | 1889 (1889) |

| Bookish affiliations | Columbia University NAICU Seven Sisters Annapolis Group Oberlin Group Space-grant |

| Endowment | $356.6 million (2020)[1] |

| President | Sian Beilock |

| Academic staff | 330 (2020)[2] |

| Undergraduates | ii,744 (2020)[three] |

| Location | New York City New York Usa 40°48′35″N 73°57′49″W / 40.8096°North 73.9635°W / twoscore.8096; -73.9635 Coordinates: xl°48′35″N 73°57′49″W / xl.8096°N 73.9635°Westward / xl.8096; -73.9635 |

| Campus | Urban |

| Colors | Blue and white |

| Sporting affiliations | NCAA Sectionalization I – Ivy League (consortium with Columbia University) |

| Mascot | Millie the Conduct[iv] |

| Website | barnard |

| |

Barnard Higher of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by Annie Nathan Meyer every bit a response to Columbia University's refusal to admit women and is named after Columbia's 10th president, Frederick Barnard.

Barnard is one of four undergraduate colleges of Columbia University but has legal and fiscal autonomy. Students share classes, clubs, fraternities and sororities, sports[five] teams, buildings, and more with Columbia, and receive a Columbia diploma that is signed by both Barnard and Columbia presidents.

Barnard offers Available of Arts degree programs in about 50 areas of written report. Students may as well pursue elements of their education at Columbia, the Juilliard Schoolhouse, the Manhattan Schoolhouse of Music, and The Jewish Theological Seminary, which are also based in New York City. Its four-acre (1.6 ha) campus is located in the Upper Manhattan neighborhood of Morningside Heights, stretching along Broadway between 116th and 120th Streets. Information technology is directly beyond from Columbia'south main campus and nearly several other academic institutions.

The higher is one of the original 7 Sisters, vii highly selective liberal arts colleges in the northeastern United States that were historically women'south colleges. (Five currently be as women's colleges.)

History [edit]

Founding [edit]

Members of the Barnard class of 1913

For its first 229 years Columbia Higher of Columbia University admitted just men for undergraduate study.[half dozen] Barnard College was founded in 1889 every bit a response to Columbia's refusal to admit women into its institution.

The college was named afterward Frederick Augustus Porter Barnard, a deaf American educator and mathematician who served as the tenth president of Columbia from 1864 to 1889. He advocated for equal educational privileges for men and women, preferably in a coeducational setting, and began proposing in 1879 that Columbia admit women.[vii]

Columbia's Board of Trustees repeatedly rejected Barnard's suggestion,[vii] just in 1883 agreed to create a detailed syllabus of report for women. While they could non nourish Columbia classes, those who passed examinations based on the syllabus would receive a degree. The first such woman graduate received her bachelor's degree in 1887. A former educatee of the program, Annie Meyer,[eight] and other prominent New York women persuaded the lath in 1889 to create a women'south college connected to Columbia.[7] [9]

Men and women were evenly represented amid the founding Trustees of Barnard College. The males were Rev. Dr. Arthur Brooks (chair of the board), Silas B. Brownell, Frederick R. Coudert, Noah Davis, George Hoadley, Hamilton Westward. Mabie, George Arthur Plimpton, Jacob Schiff, Francis Lynde Stetson, Henry Van Dyke, and Everett P. Wheeler.[10] : 212 The founding female trustees of Barnard College were Augusta Arnold (née Foote), Helen Dawes Brownish, Virginia Brownwell (née Swinburne), Caroline Sterling Choate, Annie Nathan Meyer, Laura Rockefeller, Clara C. Stranahan (née Harrison), Henrietta East. Talcott (née Francis), Ella Weed, Alice Williams, and Frances Fisher Wood.[11] [10] : 212

Barnard Higher's original 1889 home was a rented brownstone at 343 Madison Artery, where a faculty of vi offered instruction to xiv students in the Schoolhouse of Arts, every bit well as to 22 "specials", who lacked the entrance requirements in Greek so enrolled in science.[12]

Morningside campus [edit]

When Columbia University announced in 1892 its impending move to Morningside Heights, Barnard built a new campus nearby with gifts from Mary E. Brinckerhoff, Elizabeth Milbank Anderson and Martha Fiske.[13] Two of these gifts were made with several stipulations fastened. Brinckerhoff had offered $100,000 in 1892, on the condition that the Barnard acquire land within one,000 feet of the Columbia campus inside the next four years.[14] The Barnard trustees purchased land between 119th-120th Streets after receiving funds for that purpose in 1895.[15] [16] Anderson, who gave $170,000, requested that Charles A. Rich exist hired.[17] Rich designed the Milbank, Brinckerhoff, and Fiske Halls, built in 1897–1898;[17] these were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2003.[eighteen] The first classes at the new campus were held in 1897. Despite Brinckerhoff'southward, Anderson'south, and Fiske's gifts, Barnard remained in debt.[thirteen]

Ella Weed supervised the college in its showtime four years; Emily James Smith succeeded her as Barnard's first dean.[7] Jessica Finch is credited with coining the phrase "current events" while educational activity at Barnard College in the 1890s.[19]

As the college grew it needed additional infinite, and in 1903 information technology received the three blocks south of 119th Street from Anderson who had purchased a one-time portion of the Bloomingdale Asylum site from the New York Infirmary.[twenty] [21] Rich provided a master plan for the campus, but simply Brooks Hall was built, being constructed between 1906 and 1908.[22] [23] None of Rich's other plans were carried out. Students' Hall, at present known every bit Barnard Hall, was congenital in 1916 to a design by Arnold Brunner.[24] Hewitt Hall was the final structure to be erected, in 1926–1927.[23] All 3 buildings were listed on the National Register of Celebrated Places in 2003.[18] [25] An inability to heighten funds precluded the construction of whatever other buildings.[25]

By the mid-20th century Barnard had succeeded in its original goal of providing a top-tier education to women. Between 1920 and 1974, but the much larger Hunter College and University of California, Berkeley produced more women graduates who later received doctorate degrees.[26] In the 1970s, Barnard faced considerable pressure to merge with male only Columbia College, which was fiercely resisted by its president, Jacquelyn Mattfeld.[27]

Academics [edit]

Barnard students are able to pursue a Available of Arts degree in nearly 50 areas of study.[28] Joint programs for the Bachelor of Science and other degrees exist with Columbia University, Juilliard School, and The Jewish Theological Seminary. The virtually popular majors at the college include Economics, English, Political Science, History, Psychology, Biological Sciences, Neuroscience, and Computer Science.[29]

The liberal arts general education requirements are collectively called Foundations. Students must take 2 courses in the sciences (1 of which must be accompanied past a laboratory course), report a single strange language for two semesters, and take 2 courses in the arts/humanities equally well as two in the social sciences. In addition, students must consummate at least one three-credit class in each of the post-obit categories, known as the Modes of Thinking: Thinking Locally—New York City, Thinking through Global Enquiry, Thinking about Social Departure, Thinking with Historical Perspective, Thinking Quantitatively and Empirically, and Thinking Technologically and Digitally. The use of AP or IB credit to fulfill these requirements is very express, but Foundations courses may overlap with major or minor requirements. In addition to the distributional requirements and the Modes of Thinking, students must complete a starting time-year seminar, a kickoff-twelvemonth writing course, and ane semester of concrete education. Foundations replaced the old general teaching requirements, called the Nine Means of Knowing, in 2016.[30]

Admissions [edit]

| 2022[31] | 2021[31] | 2020[31] | 2019[32] | 2018[33] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 12,009 | 10,395 | 9,411 | 9,320 | seven,897 |

| Admits | NA | ane,084 | 1,022 | ane,097 | 1,099 |

| Admit charge per unit | viii% | 10% | 10.viii% | 11.8% | 13.9% |

| Enrolled | Northward/A | N/A | N/A | 632 | 605 |

| Sat mid-fifty% range* | North/A | N/A | N/A | 1360-1500 | 1330-1500 |

| Human action mid-50% range | N/A | Due north/A | N/A | 31-34 | 30-33 |

| * SAT out of 1600 |

Admissions to Barnard is considered almost selective by U.S. News & World Study.[34] It is the nearly selective women's college in the nation;[35] in 2017, Barnard had the lowest acceptance rate of the five Seven Sisters that remain single-sex activity in admissions.[36]

The class of 2026'southward access rate was 8% of the 12,009, the lowest acceptance rate in the institution's history.[37] The median SAT Composite score of enrolled students was 1440, with median subscores of 720 in Math and 715 in Evidence-Based Reading and Writing.[32] The median ACT Composite score was 33.[32]

In 2015 Barnard announced that information technology would acknowledge transgender women who "consistently live and identify as women, regardless of the gender assigned to them at nascence", and would continue to support and enroll those students who transitioned to males later on they had already been admitted.[38]

Rankings [edit]

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Liberal arts colleges | |

| U.South. News & World Written report [39] | 17 |

| Washington Monthly [xl] | 24 |

| National | |

| Forbes [41] | 50 |

| THE/WSJ [42] | 59 |

Barnard is ranked tied at 17th overall, tied for 16th in "Most Innovative Schools", tied for 64th for "Best Undergraduate Didactics," and 38th schools for "All-time Value" for 2022 among U.S. liberal arts colleges by U.S. News & Earth Report.[43] Forbes ranked Barnard the 19th best liberal arts higher in 2019, which also ranked it 50th among 650 universities, liberal arts colleges and service academies.[44]

Campus [edit]

Library [edit]

Milbank Hall

While students are immune to use the libraries at Columbia Academy, Barnard has always maintained a library of its ain. Lehman Hall was the site of Barnard's Wollman Library from its opening in 1959 until 2015.[45] In Baronial 2016, Lehman Hall was demolished to make fashion for a new library facility.[46] Barnard'south Milstein Center for Teaching and Learning opened in September 2018.[47] In 2016, portions of the Barnard Library were relocated to the one-time LeFrak Gymnasium, the first two floors of Barnard Hall.[48] 18,000 volumes were also moved to the Milstein rooms in Columbia Academy's Butler Library.[49] The relocation plans proved to be contentious among faculty at the college, who objected to sending a large portion of the library's holdings off site, every bit well as a "lack of transparency surrounding the decision-making process", according to Library Periodical.[45]

The LeFrak Center housed study infinite, librarians' offices, the zine collection, class reserves, and new books caused after July 2015-.[50] The Barnard Library also encompasses the Archives and Special Collections, a repository of official and student publications, photographs, letters, alumnae scrapbooks and other material that documents Barnard's history from its founding in 1889 to the nowadays day.[51] Among the collections are the Ntozake Shange papers[52] and various student publications.[53]

Barnard Public Safety Shuttle operates around the campus expanse.

Zine Drove [edit]

Borne of a proposal by longtime zinester Jenna Freedman, Barnard collects zines in an attempt to document 3rd-wave feminism and Riot Grrrl civilisation.[ non-master source needed ] According to Freedman, zine collections such every bit Barnard's provide a dwelling house for the voices of immature women otherwise not represented in library collections.[54] The Zine Collection's website states:

"Barnard's zines are created by womxn and non-binary people, a collection emphasis on by women of colour and a new (2019) attempt to learn more zines past transwomen. We collect zines on feminism and femme identity by people of all genders. The zines are personal and political publications on activism, anarchism, body paradigm, gender, parenting, queer community, riot grrrl, sexual assault, trans feminisms, and other topics.".[55]

Equally of June 2015[update], the library had approximately 4,000 different zines available to library patrons,[56] including zines nigh race, gender, sexuality, childbirth, maternity, politics, and relationships. The library keeps a collection of zines for lending and another archived collection in the Barnard Athenaeum. Both collections are catalogued in CLIO, the Columbia/Barnard Online public access catalog.[57]

Student life [edit]

Educatee organizations [edit]

College life every bit depicted past the college's newspaper in 1923.

A 1902 delineation of a "modern" Barnard woman.

A depiction of the Barnard Bear, commonly referred to by students every bit Millie the Dancing Conduct.

Every Barnard student is part of the Student Government Association (SGA), which elects a representative student government. SGA aims to facilitate the expression of opinions on matters that direct bear on the Barnard community.[58]

Student groups include theatre and vocal music groups, language clubs, literary magazines, a freeform radio station chosen WBAR, a biweekly mag called the Barnard Bulletin, community service groups, and others.

Barnard students can likewise join extracurricular activities or organizations at Columbia University, while Columbia Academy students are allowed in most, simply not all, Barnard organizations. Barnard's McIntosh Activities Council (normally known as McAC), named after the first President of Barnard, Millicent McIntosh, organizes various community focused events on campus, such as Big Sub and Midnight Breakfast. McAC is made up of five sub-committees which are the Mosaic committee (formerly known as Multicultural), the Wellness committee, the Network commission, the Customs committee, and the Action committee. Each committee has a different focus, such as hosting and publicizing identity and cultural events (Mosaic), having health and health related events (Wellness), giving students opportunities to exist involved with Alumnae and diverse professionals (Network), planning events that bring the entire student torso together (Community), and planning community service events that give back to the surrounding community (Activeness).

Sororities [edit]

Barnard students participate in Columbia'due south six National Panhellenic Conference sororities—Alpha Chi Omega, Alpha Omicron Pi, Delta Gamma, Gamma Phi Beta, Kappa Alpha Theta, and Sigma Delta Tau—and the National Pan-Hellenic Council Sororities- Alpha Kappa Alpha (Lambda chapter) and Delta Sigma Theta (Rho affiliate) as well as other sororities in the Multicultural Greek Council. Two National Panhellenic Conference organizations were founded at Barnard College. The Blastoff Omicron Pi fraternity, founded on January 2, 1897, left campus during the higher's 1913 ban[59] on sororities but returned to establish its Blastoff affiliate in 2013. The Blastoff Epsilon Phi, founded on October 24, 1909, is no longer on campus. As of 2010[update], Barnard does non fully recognize the National Panhellenic Briefing sororities at Columbia, merely information technology does provide some funding to account for Barnard students living in Columbia housing through these organizations.[60]

Traditions [edit]

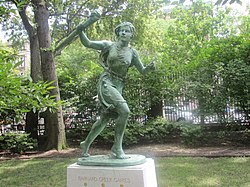

Barnard Greek Games: Ane of Barnard's oldest traditions, the Barnard Greek Games were first held in 1903, and occurred annually until the Columbia University protests in 1968. Since then they have been sporadically revived. The games consist of competitions betwixt each graduating grade at Barnard, and events have traditionally included Greek poesy recitation, dance, chariot racing, and a torch race.[61]

Accept Back the Night: Each April, Barnard and Columbia students participate in the Take Dorsum the Dark march and speak-out. This annual event grew out of a 1988 Seven Sisters conference. The march has grown from under 200 participants in 1988 to more than than ii,500 in 2007.[62]

Midnight Breakfast marks the kickoff of finals week. As a highly popular event and long-standing higher tradition, Midnight Breakfast is hosted by the educatee-run activities council, McAC (McIntosh Activities Council). In addition to providing standard breakfast foods, each year's theme is too incorporated into the bill of fare. By themes have included "I YUMM the 90s," "Grease," and "Take Me Out to the Ballgame." The upshot is a school-broad affair every bit higher deans, trustees and the president serve nutrient to nigh a thousand students. It takes place the night before finals begin every semester.[63]

Big Sub: Towards the get-go of each fall semester, Barnard College supplies a 700+ feet long subway sandwich. Students from the college can have equally much of the sub as they tin can comport. The sub has kosher, dairy gratis, vegetarian, and vegan sections. This event is organized past the pupil-run activities quango, McAC.[64]

Academic affiliations [edit]

Relationship with Columbia University [edit]

Greek Games statue

Front gates read "Barnard Higher of Columbia Academy"

The Barnard Bulletin in 1976 described the relationship between the college and Columbia University as "intricate and ambiguous".[65] Barnard president Debora Spar said in 2012 that "the relationship is admittedly a complicated one, a unique ane and i that may take a few sentences to explicate to the outside community".[66]

Outside sources often draw Barnard as function of Columbia; The New York Times in 2013, for example, called Barnard "an undergraduate women's higher of Columbia University".[7] [67] Its front gates read "Barnard College of Columbia Academy."[68] Barnard describes itself as "both an independently incorporated educational institution and an official higher of Columbia Academy"[69] that is "one of the Academy's four colleges, but nosotros're largely autonomous, with our own leadership and purse strings",[70] and advises students to country "Barnard College, Columbia University" or "Barnard College of Columbia University" on résumés.[71] Facebook includes Barnard students and alumnae inside the Columbia interest group.[72]

Columbia describes Barnard as an affiliated establishment[73] that is a faculty of the university[74] or is "in partnership with" it.[75] Both the college and Columbia evaluate Barnard faculty for tenure,[76] and Barnard graduates receive Columbia diplomas signed by the Barnard and the Columbia presidents.[77] [78]

Before coeducation at Columbia [edit]

Smith and Columbia president Seth Low worked to open Columbia classes to Barnard students. By 1900 they could attend Columbia classes in philosophy, political scientific discipline, and several scientific fields.[7] That year Barnard formalized an affiliation with the academy which made available to its students the instruction and facilities of Columbia.[69] Franz Boas, who taught at both Columbia and Barnard in the early 1900s, was among those kinesthesia members who reportedly plant Barnard students superior to their male Columbia counterparts.[26] From 1955 Columbia and Barnard students could register for the other school'due south classes with the permission of the teacher; from 1973 no permission was needed.[eight]

Except for Columbia College, by the 1940s other undergraduate and graduate divisions of Columbia University admitted women.[half dozen] Columbia president William J. McGill predicted in 1970 that Barnard Higher and Columbia Higher would merge within 5 years. In 1973 Columbia and Barnard signed a 3-year agreement to increase sharing classrooms, facilities, and housing, and cooperation in faculty appointments,[79] which they described as "integration without assimilation";[eighty] by the mid-1970s virtually Columbia dormitories were coed.[81] The university'south financial difficulties during the decade increased its desire to merge[82] to end what Columbia described as the "anachronism" of single-sex educational activity,[80] but Barnard resisted doing so because of Columbia's big debt,[81] rejecting in 1975 Columbia dean Peter Pouncey'due south proposal to merge Barnard and the three Columbia undergraduate schools.[79] The 1973–1976 chairwoman of the lath at Barnard, Eleanor Thomas Elliott, led the resistance to this takeover.[83] The college's marketing emphasized the Columbia relationship, yet, the Bulletin in 1976 stating that Barnard described it every bit identical to the 1 between Harvard College and Radcliffe College ("who are merged in practically everything just name at this betoken").[65]

After Barnard rejected subsequent merger proposals from Columbia and a one-year extension to the 1973 agreement expired, in 1977 the two schools began discussing their hereafter relationship. By 1979 the relationship had then deteriorated that Barnard officials stopped attending meetings. Because of an expected decline in enrollment, in 1980 a Columbia committee recommended that Columbia College brainstorm albeit women without Barnard's cooperation. A 1981 committee found that Columbia was no longer competitive with other Ivy League universities without women, and that admitting women would not affect Barnard'south applicant pool. That year Columbia president Michael Sovern agreed for the two schools to cooperate in admitting women to Columbia, but Barnard kinesthesia'due south opposition acquired president Ellen Futter to reject the agreement.[79]

A decade of negotiations for a Columbia-Barnard merger akin to Harvard and Radcliffe had failed.[80] In January 1982, the two schools instead announced that Columbia College would begin admitting women in 1983, and Barnard's command over tenure for its faculty would increase;[79] [six] previously, a committee on which Columbia faculty outnumbered Barnard's three to two controlled the latter'south tenure.[80] Applications to Columbia rose 56% that year, making admission more selective, and nine Barnard students transferred to Columbia. Eight students admitted to both Columbia and Barnard chose Barnard, while 78 chose Columbia.[84] Inside a few years, notwithstanding, selectivity rose at both schools as they received more women applicants than expected.[six]

After coeducation [edit]

The Columbia-Barnard affiliation connected.[80] Equally of 2012[update] Barnard pays Columbia about $v one thousand thousand a yr under the terms of the "interoperate relationship", which the ii schools renegotiate every xv years.[66] Despite the affiliation Barnard is legally and financially separate from Columbia, with an independent faculty and board of trustees. It is responsible for its own carve up admissions, health, security, guidance and placement services, and has its own alumnae association. All the same, Barnard students participate in the academic, social, athletic and extracurricular life of the broader University community on a reciprocal basis. The amalgamation permits the two schools to share some academic resources; for instance, just Barnard has an urban studies section, and merely Columbia has a information science department. Almost Columbia classes are open up to Barnard students and vice versa. Barnard students and kinesthesia are represented in the Academy Senate, and student organizations such as the Columbia Daily Spectator are open up to all students. Barnard students play on Columbia athletics teams, and Barnard uses Columbia electronic mail, telephone and network services.[66] [78]

Barnard athletes compete in the Ivy League (NCAA Division I) through the Columbia/Barnard Athletic Consortium, which was established in 1983. Through this system, Barnard is the merely women's college offering SectionalisationI athletics.[85] There are fifteen intercollegiate teams, and students also compete at the intramural and club levels. From 1975 to 1983, earlier the institution of the Columbia/Barnard Athletic Consortium, Barnard students competed equally the "Barnard Bears".[86] Prior to 1975, students referred to themselves every bit the "Barnard honeybears".[87]

Controversies [edit]

In the bound of 1960, Columbia University president Grayson Kirk complained to the president of Barnard that Barnard students were wearing inappropriate clothing. The garments in question were pants and Bermuda shorts. The administration forced the student council to establish a dress code. Students would be allowed to wear shorts and pants only at Barnard and just if the shorts were no more than than two inches in a higher place the knee joint and the pants were not tight. Barnard women crossing the street to enter the Columbia campus wearing shorts or pants were required to embrace themselves with a long glaze.[88] [89]

In March 1968, The New York Times ran an article on students who cohabited, identifying one of the persons they interviewed as a student at Barnard College from New Hampshire named "Susan".[90] Barnard officials searched their records for women from New Hampshire and were able to determine that "Susan" was the pseudonym of a student (Linda LeClair) who was living with her boyfriend, a pupil at Columbia University. She was called before Barnard's pupil-kinesthesia assistants judicial committee, where she faced the possibility of expulsion. A student protest included a petition signed by 300 other Barnard women, admitting that they likewise had broken the regulations against cohabitating. The judicial committee reached a compromise and the student was allowed to remain in school, but was denied use of the college cafeteria and barred from all social activities. The student briefly became a focus of intense national attending. She eventually dropped out of Barnard.[8] [91] [92]

Assistants [edit]

The post-obit lists all the presidents and deans of Barnard College from 1889 to present.[93] [94]

- Ella Weed (1889–1894)

- Emily James Smith (1894–1900)

- Laura Drake Gill (1901–1907)

- Virginia Gildersleeve (1911–1947)

- Millicent McIntosh (1952–1962)

- Rosemary Park (1962–1967)

- Martha Peterson (1967–1975)

- Jacquelyn Mattfeld (1976–1981)

- Ellen Futter (1981–1993)

- Judith Shapiro (1994–2008)

- Debora Spar (2008–2017)

- Sian Beilock (2017–present)

Notable people [edit]

Barnard College has graduated many prominent leaders in science, religion, politics, the Peace Corps, medicine, law, education, communications, theater, and business; and acclaimed actors, architects, artists, astronauts, engineers, human rights activists, inventors, musicians, philanthropists, and writers. Amongst these include: bookish Louise Holland (1914), author Zora Neale Hurston, author and political activist Grace Lee Boggs (1935), television receiver host Ronnie Eldridge (1952), Phyllis E. Grann CEO of Penguin Putnam,[95] U.S. Representative Helen Gahagan (1924), CEO of Intendance United states and chair of the Presidential Advisory Quango on HIV/AIDS Helene D. Gayle (1970), President of the American Civil Liberties Union Susan Herman (1968), Primary Guess of the New York Court of Appeals Judith Kaye (1958), Chair of the National Labor Relations Lath Wilma B. Liebman (1971), musician and performance creative person Laurie Anderson (1969), actress, activist and gubernatorial candidate Cynthia Nixon (1988), author of The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants Ann Brashares (1989), The New Yorker Cartoonist Amy Hwang (2000), actress from Grayness's Anatomy Kelly McCreary (2003), author and manager Greta Gerwig (2004), and Disney Aqueduct extra Christy Carlson Romano (2015).

-

-

Laurie Anderson '69, performance artist and NASA's first Artist-in-Residence

-

-

-

Katherine Boo '88, journalist and recipient of the Pulitzer and MacArthur Foundation prizes

See also [edit]

- Athena Film Festival

- Barnard Center for Research on Women

- Hidden Ivies: Thirty Colleges of Excellence

- Women's colleges in the Us

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ As of June 30, 2020. U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2020 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY19 to FY20 (Report). National Clan of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. February 19, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Barnard Higher Mutual Data Ready 2020-2021" (PDF). Barnard College.

- ^ "Barnard College Common Data Ready 2020-2021" (PDF). Barnard College.

- ^ "At-a-Glance". Barnard College. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ "Athletics". Women's NCAA Athletics. Barnard College. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Farmer, Melanie. "College Marks 25 years of Coeducation". The Record . Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Weneck, Bette (Bound 1991). "Social and Cultural Stratification in Women's Higher Education: Barnard Higher and Teachers College, 1898–1912". History of Education Quarterly. 31 (1): 1–25. doi:x.2307/368780. JSTOR 368780.

- ^ a b c Rosenberg, Rosalind (September 21, 1999). "The Woman Question". Barnard College. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ^ "First Barnard Board of Trustees, 1889". Alma Mater: The History of American Colleges & Universities . Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b Putnam, Emily Jane (1900). "The rise of Barnard Higher". Columbia University Quarterly. II (3): 209–217. Retrieved July two, 2020.

- ^ Pinsky, Paulina Marie (Feb 23, 2015). "Barnard's Original Women Trustees Original Women on the Lath of Trustees". Columbia Academy . Retrieved July ii, 2020.

- ^ "Barnard College: An Early Timeline, To 1939 | Barnard 125". Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Dolkart 1998, p. 215.

- ^ Dolkart 1998, p. 209.

- ^ Dolkart 1998, p. 210.

- ^ "GIFTS TO BARNARD College; Two HUNDRED THOUSAND DOLLARS FOR A Edifice FUND. Money Needed for State on Morningside Heights -- Money Guaranteed for Post-Graduate Professors". The New York Times. February 19, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Dolkart 1998, pp. 211–214.

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Annals of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Mrs. John Cosgrave Is Dead Founded Finch Junior Higher: Was Institution'due south President Nearly l Years; Coined 'Current Events' Phrase". New York Herald Tribune. November 1, 1949.

- ^ Plimpton Papers, Barnard College Archives

- ^ Dolkart 1998, p. 217.

- ^ Dolkart 1998, pp. 218–219.

- ^ a b Kathleen A. Howe (June 2003). "National Register of Celebrated Places Registration: Brooks and Hewitt Halls". New York Country Role of Parks, Recreation and Celebrated Preservation. Retrieved March nineteen, 2011.

- ^ Dolkart 1998, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Dolkart 1998, p. 223.

- ^ a b Zimmerman, Jonathan (March 14, 2012). "Barnard College flap: Competition amidst women shouldn't be over men". Christian Science Monitor . Retrieved March ane, 2013.

- ^ Maeroff, Gene I. (May 30, 1980). "Necktie to Columbia Called Big Event In Mattfeld Shift; Barnard President Seen as Likewise Intensely Opposed Areas of Disagreement Autonomy and Amalgamation Turnover in Personnel". The New York Times.

- ^ "Barnard at a Glance". Barnard College. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ "Facts & Stats | Barnard College". barnard.edu . Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ "Foundations | Barnard College". barnard.edu . Retrieved Nov 12, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Barnard College Admits one,084 to the Grade of 2025". Barnard College. Retrieved March xxx, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Barnard College Common Data Set 2019-2020, Part C" (PDF). Barnard College. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Barnard College Common Information Set 2018-2019, Part C" (PDF). Barnard Higher. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ U.South. News & World Report https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/barnard-higher-2708. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ Barnard Higher (March 23, 2017). "Nation's Elevation Women'due south Higher Admits Most Selective Class in 127 Year History". Barnard Website . Retrieved December half dozen, 2017.

- ^ "Rankingsandreviews.com". Colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com. Retrieved February xx, 2011.

- ^ Sentner, Irie. "Barnard accepts tape-depression 8 percentage of applicants to its nigh diverse class always - Columbia Spectator". Columbia Daily Spectator . Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "Barnard College volition now accept transgender women". CNN. June iv, 2015.

- ^ "Best Colleges 2021: National Liberal Arts Colleges". U.S. News & World Study . Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "2021 Liberal Arts Rankings". Washington Monthly . Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2021". Forbes . Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ "Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education Higher Rankings 2021". The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Instruction . Retrieved October xx, 2020.

- ^ "Barnard College Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "America'southward Top Colleges". Forbes. Baronial 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Peet, Lisa (January 22, 2015). "Plans for New Barnard Library Bear witness Divisive". Library Periodical.

- ^ "Facilities: Buildings". New York, N.Y.: Barnard College. Archived from the original on Baronial 31, 2016.

- ^ "Educational activity and Learning Center: New Building FAQs". New York, Due north.Y.: Barnard Higher. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved September xv, 2016.

- ^ "Educational activity and Learning Center: LeFrak Center". New York, Northward.Y.: Barnard College. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ "Barnard Books in Milstein Rooms at Butler Library". BLAIS. barnard.edu. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ "Follow Your Centre to the LeFrak Center". BLAIS. barnard.edu. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ "About United states". BLAIS. barnard.edu. Archived from the original on July xv, 2016. Retrieved June xxx, 2016.

- ^ Schuessler, Jennifer (April 15, 2016). "Ntozake Shange Archive Goes to Barnard". New York Times . Retrieved June thirty, 2016.

- ^ "Digital Exhibit of Barnard Publications". BLAIS. barnard.edu. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Freedman, Jenna (2009). "Grrrl Zines in the Library". Signs. 35 (one): 52–59. doi:10.1086/599266. JSTOR x.1086/599266. S2CID 145208834.

- ^ "About Zines at Barnard". New York, N.Y.: Barnard Zine Collection; Barnard Higher. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ "About the Collection". New York, N.Y.: Barnard Zine Drove; Barnard College. Archived from the original on September fifteen, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ "About United states of america: Our Collections". New York, Northward.Y.: Barnard Library. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ "Student Government Association | Barnard College". barnard.edu . Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Barnard Fraternity Ban of 1913". Sororities- Barnard Archives and Special Collections. Barnard Athenaeum and Special Collections. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Barnard funding for sororities, simply not recognition | Columbia Daily Spectator. Columbiaspectator.com. Retrieved on September 7, 2013.

- ^ Bandrowski, Ainsley (April xx, 2017). "Barnard Greek Games to return after four years". Columbia Daily Spectator . Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ Nicholas Bergson-Shilcock (March 16, 2007). "Take Back the Night". Columbia.edu. Retrieved Feb 20, 2011.

- ^ "A Barnard Tradition: Midnight Breakfast | Barnard College". barnard.edu . Retrieved June xi, 2016.

- ^ "Customs-Student Life". Barnard. Archived from the original on Apr 26, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ a b "Is the Customer E'er Right?". Barnard Bulletin (Editorial). February i, 1976. p. 8. Retrieved Feb iii, 2016.

- ^ a b c Stallone, Jessica. "Barnard, CU legally bound, only human relationship not e'er certain for students". Columbia Spectator . Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ Kaminer, Ariel; Leonard, Randy (May 9, 2013). "Reports of Cheating at Barnard Cause a Stir". The New York Times. pp. A25. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved January four, 2016.

- ^ Teichman, Alysa (October 29, 2008). "50 Most Expensive Colleges / Barnard Higher". Bloomberg Businessweek . Retrieved Dec 8, 2012.

- ^ a b "Barnard College Course Catalogue". Barnard.edu. Archived from the original on Feb 21, 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Our Partnership with Columbia Academy". Barnard College . Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ "Resume and Cover Letter of the alphabet Samples". Beyond Barnard Online Career Resources. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ "Why is Barnard role of the Columbia network?". Alumnae Affairs, Barnard College. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ [i] "Undergraduate education at Columbia is offered through Columbia Higher, the Fu Foundation Schoolhouse of Engineering and Engineering, and the School of General Studies. Undergraduate programs are offered past two affiliated institutions, Barnard College and Jewish Theological Seminary."

- ^ "Organisation and Governance of the Academy". Faculty Handbook 2008. Columbia University. November 2008. Retrieved July five, 2012.

- ^ "Often Asked Questions – Engineering". Undergraduate Admissions, Columbia Academy. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Principles and Customs Governing the Procedures of Ad Hoc Committees and University-Wide Tenure Review. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- ^ "Charters and Statutes" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Almost the College: Partnership with Columbia". Barnard College. 2011. Archived from the original on Feb eighteen, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d "The Route to Coeducation". Columbia Spectator. August 29, 1983. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Columbia Decides to Go Coed". Time. Feb 1, 1982. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009.

- ^ a b "A Survey of Co-education in The Ivies". Harvard Crimson. October iv, 1974. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ Hartocollis, Anemona (September 24, 1975). "Financial Difficulties Prompt Columbia Report on Merger". Harvard Crimson . Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ "Eleanor Thomas Elliott, 80, Barnard Figure". The New York Times. December 6, 2006. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ Belkin, Lisa (September ii, 1983). "First Women Enrolled at Columbia College". The Palm Beach Mail. New York Times. pp. B8. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ "Athletics".

- ^ "magazine-spring09/half dozen". Issuu.com. May eighteen, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Columbia Daily Spectator 21 February 1964 — Columbia Spectator". spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu . Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Ban on Shorts Threatens Classic Barnard Couture". The New York Times. Apr 28, 1960. p. 1.

- ^ "Administrative Regulations: Campus Etiquette". Barnard College Blue Volume. pp. 87–88.

- ^ Klemesrud, Judy (March 4, 1968). "An arrangement: living together for convenience, security, sex". The New York Times.

- ^ Newsweek, April 8, 1968, p. 85 and Newsweek, April 29, 1968, p. 79-80.

- ^ Bailey, Beth L. (1999). Sex in the heartland. Harvard University Press. p. 201. ISBN0-674-00974-6.

- ^ "Past Presidents". Archived from the original on November 25, 2011. Retrieved September xviii, 2011.

- ^ Harris, Elizabeth A. (May 22, 2017). "Barnard Chooses a Leader Whose Research Focuses on Women". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ Maneker, Marion (January i, 2002). "Now for the Grann Finale". New York Magazine . Retrieved May 23, 2018.

Sources [edit]

- Dolkart, Andrew S. (1998). Morningside Heights: A History of its Architecture and Development. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN978-0-231-07850-4. OCLC 37843816.

- Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz (1993). Alma Mater: Design and Feel in the Women's Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s (2d edition). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Printing.

External links [edit]

- Official website

- Video on Barnard College: The Early Years (1889–1929) on YouTube

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barnard_College

0 Response to "Ms Pouleur Received a Bachelor of Arts From Barnard"

Post a Comment